Dot Slash Hack

Dot Slash Hack (aka ./#) is a MMORPG where players have the ability to write their own spells in JavaScript. It was envisioned to persuade players to learn programming in order to have greater control in the game, something which I had seen happen with players in Minecraft, who memorize many crafting recipes throughout their play-time.

I made a lot of decisions in the beginning of this project to try to make it as scalable and easy-to-maintain by a team of developers as possible. This was to be in case it blew up and I ended up becoming filthy rich as the head of my own company, but also because I wanted to write a project with that in mind from the beginning.

Backend

The backend for ./# was programmed in NodeJs. This was mostly because I wanted to write something in NodeJs at the time, but had the additional benefit of giving me a write-once ability which linked the front-end and back end with the same code. Since it was all in JavaScript, I could just Browserify the classes I needed to include in the client.

Database

I used the database PostgreSQL for a similar reason, I wanted to use something different than what I used at work. While not using an ORM like Sequelize gave me a lot of query-writing experience, if I were to rewrite ./#, I would use Sequelize specifically to handle the user persistence.

The entities other than the Users don’t actually get persisted in the DB, so there wasn’t a whole lot of database writing going on in the server.

Map

I made a fundamental decision early on away from procedurally generated map content, towards a fully user-generated map. I wanted the game to take on more of the feel of WOW or some of the other MMO’s, and not be like Minecraft. Additionally, I wanted greater control over the users’ level progression through encounters, and this let me do that.

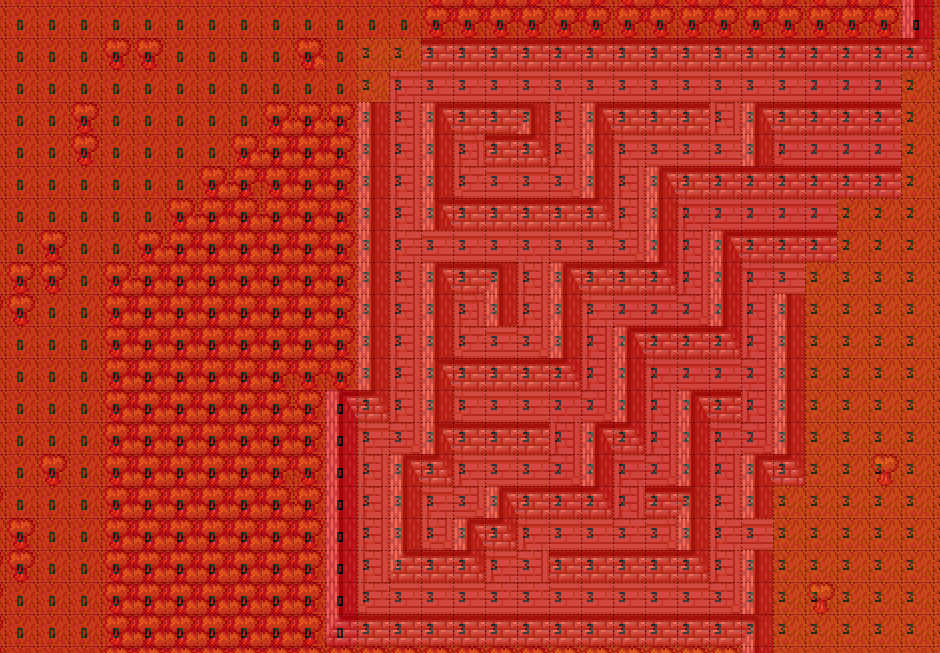

I designed the game maps using the Tiled editor, and it was just a pleasure. Each square in the game had a foreground tile (optional), a background tile, and a difficulty level which was represented as a separate layer in the map. I ended up really enjoying the decision to have the tiles determine their difficulty through a separate map tile, as I was able to have a difficulty overlay of the map at any time while designing new sections.

Additionally, the Tiled editor lets you add extra data to everything, which allowed me to not only add data on whether a player could walk through a tree to a tree tile, but to add offsetX and offsetY data to entire map sections to determine where they were in relation to the origin in the world.

Speaking of that, I also made a decision to break up my maps into sections, each of which would have data saying where to put it specifically in the global map. This was to make collaboration in a team more efficient and less prone to merge conflicts. Along those lines as well, I would have my map creation script only read the map data in as a JSON, freeing me from a tool if Tiled ever decided to go proprietary.

For the storage of these maps, I decided early on that I did not want to load the entire map into memory, since it could get very big, which prevented me from loading from a flat JSON. I ended up deciding to store the map as entries in a Redis db due to it’s speed of retrieval. Whenever a map change needed to be put in, I had to run a script to clear out the old entries from the db and replace them with the new entries generated from Tiled.

Front end

In the past I wrote a plugin called SpellScript for Bukkit, the Minecraft server modification platform. It allowed you to code up spells in JavaScript, and was the inspiration for this server. However, there was a huge security flaw with the plugin: the scripts written by players were executed on the server. While I tried to sandbox the environment as best I could, you can never be sure there wasn’t some way of breaking out of the sandbox and hurting the server’s files.

DotSlashHack was designed from the ground up to address this vulnerability. There is an airgap between the scripts that the players write, and the code that is run on the server: nothing written by a user will ever be evaluated on server hardware. The way this was accomplished was by writing an entire api for the spells to access through a WebSocket connection (I used socket.io). Everything the spells did had to be requested through this api, from moving to damaging other entities. The logic for every request was double-checked on the server to make sure it made sense. Additionally, a rate-limiter was implemented for most spell and user actions, so a user couldn’t hack their client to send movement or damage requests at a much greater rate than normal.

Difficulties

I ran into a difficulty fairly early on with the networking of the game. JavaScript, as you may know, uses a single thread to execute all code. This wasn’t a problem initially, because the server code has relatively little going on, and doesn’t take all that much time to run.

However, the way I had it initially set up, a separate socket emission was made for each of the entities visible to the player, to give the user updated data on each entity. What I didn’t know at the time was that network connections are very expensive to start, and starting 30+ connections 20 times a second for each player started slowing down the server. I ended up solving this by bundling all of the data that a user required about the entities around it into a single JSON object, and then sending that all at once to the user.