Dynamic Archived Web Services in IPFS

In this article I will be detailing how I created a web service in IPFS that had both the ability to be updated with new data and the ability to be archived forever. Additionally, I will be talking about why I took it down. The repository for the front-end (which was archived in IPFS) is here and the repository for the backend (which was hosted on Heroku) is here.

What is IPFS

IPFS(Inter-Planetary File System) is a protocol and client software that allows you to access torrented directories and files as if they were mounted in your filesystem. In the same way that a magnet link for a torrent identifies a set of files or file by it’s hash, IPFS does the same. This hash value allows you to ask a set of peers if they have parts of that file, and those peers will cache often-requested files for future requests. It’s easy to think of IPFS as a torrent program that you access through a localhost or server (https://ipfs.io/ipfs/) hosted web service. Torrents (files or folders) are identified as urls, and thus you can view html files that have links to other torrents.

IPNS

IPNS(Inter-Planetary Name Service) is the system that IPFS uses to allow you to assign a specific link to a specific file, and then change that in the future. Since the IPFS urls are hash values, they can never change. Additionally, users can’t find a file if they don’t know the hash value of that specific file. An IPNS record can be assigned to point to different files, and thus users can view the most up-to-date version of what the owner of that record wants them to view without having to know the hash of the file they will view.

IPNS records are deleted every 24-48 hours, so the publisher of that record must re-record it more often than servers delete it

The Conundrum of Dynamism in IPFS

The idea of IPFS is that it doesn’t rely on a server to serve a specific file, instead relying on all clients to serve the file like a torrent network. However, since these are all static files, we are limited in what can be done in terms of data storage. In order to create a web service that takes in new data and stores it, we must use a hybrid approach of both IPFS and a hosted web server. Additionally, the dynamic naming provided by IPNS gives us a way to progressively release newer versions of an app.

How it works

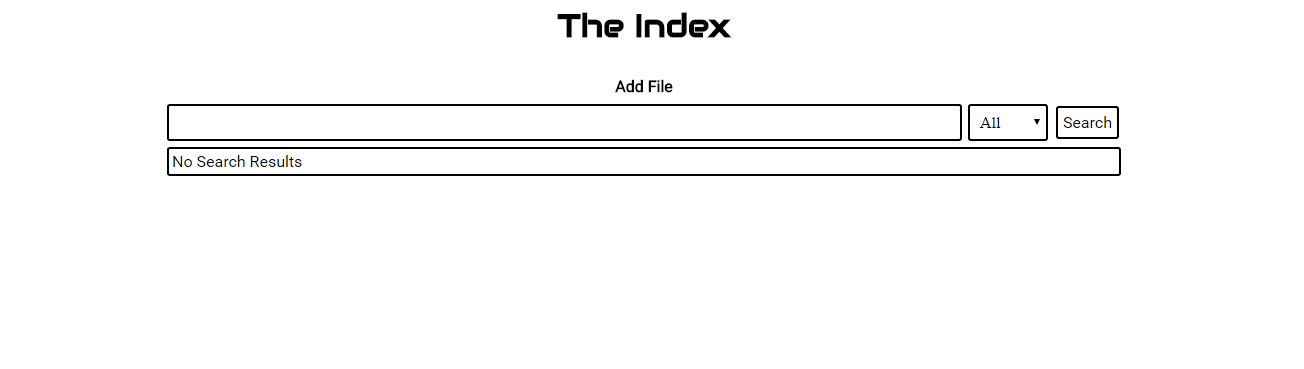

The Foundation (original name) is a React-Redux SPA meant to operate like well-known torrent websites to allow users to associate meta-information (title, type, description, etc.) with IPFS file hashes. IPFS directories, when accessed in the browser, will act like simple web directories, and will always load and display index.html if it exists. All other files required for the operation of the SPA were accessed through relative paths. Routing in React needed to use hash history since there was no web server which would route all paths to the same file.

Backend

The backend was a super simple server which exposed three API endpoints and accessed a database. It exposed an API endpoint for POSTing a new file, for POSTing a new comment, and for GETting a JSON dump of the entire database, which will be explained below.

Front-End Storage

Since I wanted the app to operate as cleanly and quickly as possible without communication to the outside internet, I integrated Google’s Lovefield database into the app to enable fast description and title searches of the downloaded JSON dump. I kept the database in-memory to prevent having to wipe the old database from the cache each time the site was accessed.

Checking for a Newer App Version

When the app was first loaded, it would see if it’s url began with ipns, and if it didn’t, it would attept to make a HEAD request to the known IPNS address that pointed to the most up-to-date app. If the url began with ipns, then we didn’t have to worry as we were already looking at the most up-to-date version of the app. A HEAD request is a special request that just retreives the response code of the url, nothing else. If the ipns url was able to be reached, I would pop up a modal asking if the user wanted to navigate to a more up-to-date version of the app, and redirect the user if they selected yes.

Getting the Data

The app tries to load data from two different locations. First, the app will try to access the backend’s API and get a JSON dump of the data. If that is unsuccessful, it will load the relative dump.json url. This json file is included in the app folder and represents the result of asking the backend server for its dump.json at compile time. Running the script scripts/publish-to-ipfs.js would download this new dump.json file and upload everything to IPFS. This was done so that if the backend server ever went down, there would still be data backed up in the app.

The structure of the folder that was linked in IPNS and published to IPFS is as follows:

/

index.html

dump.json

css

stylesheet.css

images

favicon.png

js

bundle.js

Redundancy

Instead of an IPNS link, an IPFS link to the most current version of the app was distributed. In the case that the web server was offline, the IPFS link would ask the user to update to the IPNS link, and then the app would load the most recent dump.json from IPFS, thus having a functioning database. If the IPNS hadn’t been updated recently enough and was expired, the app would still get a functioning database dump from the web server if it was still online, or the most up-to-date dump.json that it had stored. By distributing an IPFS link instead of an IPNS link I guaranteed the app would load while exposing users to the risk of getting a less up-to-date version of the dump.json in the case that the api server was down.